From légumisme to véganisme

French Vegans who are sometimes perceived like aliens can set their minds at rest: their ancestors, known as the eccentric légumistes, were regarded at best as wacky Utopians and at worst as worrying rebels. The term légumiste was originally created (in the 1750s [1]) to designate not vegetarians but gardeners who grew vegetables. Its meaning was extended to market gardening but failed to get into the Dictionnaire de l’Académie française, unlike its more common predecessor and rival maraîcher. From the 1850s, légumiste acquired a new meaning: a person who eats only vegetables. Before then there was no French word to designate vegetarians apart from phythagoricien (Pythagorean) which remained restricted due to the multiple meanings of the term (philosopher, ascetic, vegetarian, etc) [2].

The first use of the word légumiste to mean vegetarian dates from 1851 in France and Italy (legumista, plur. legumisti), reaching. Germany in 1852 (legumist, plur. legumisten) [3]. As it was rarely used in Italian or German and had already existed in French with another meaning, it most likely originated in France. Following the first ever World Fair in London, at which the existence of the British Vegetarian Society was revealed to the French, anglophile and medical French journals used the word végétarisme to refer to what more popular and polemical reviews unsurprisingly prefered to call légumisme, so légumiste prevailed for a while.

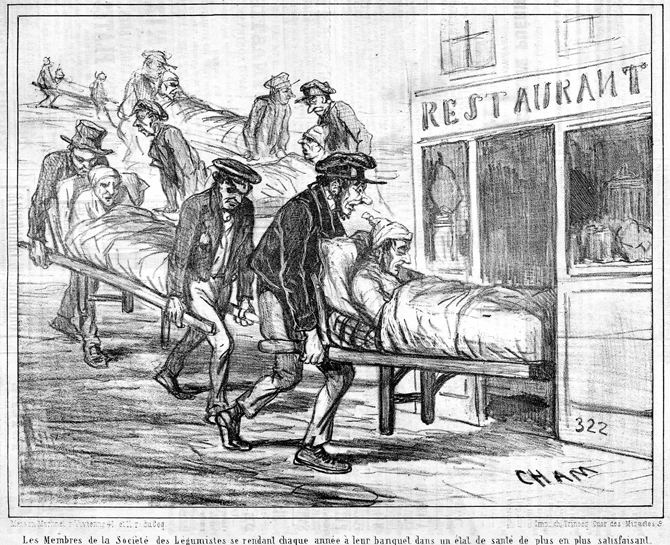

« Soirée of the Vegetarian Society, in Freemasons’ Hall » (The Illustrated London News, 16th August 1851)

At first, the term légumiste was most likely ironic, as explained in the Schweizerisches Correspondenzblatt für Aerzte und Apotheker (February 1852, vol. III, no 2): “In addition to those herbarians is the sect of the “vegetarians”, also mockingly known as the “légumistes”, who for religious reasons live only on plant foods” (« Neben diesen Herbariern existirt auch die Sekte der “Vegetarier” spottweise auch “Legumisten” genannt, welche theils aus religiösen Gründen einzig aus Pflanzennahrung leben »). According to Alfred Delvau [4], légumiste even reached French criminal slang).

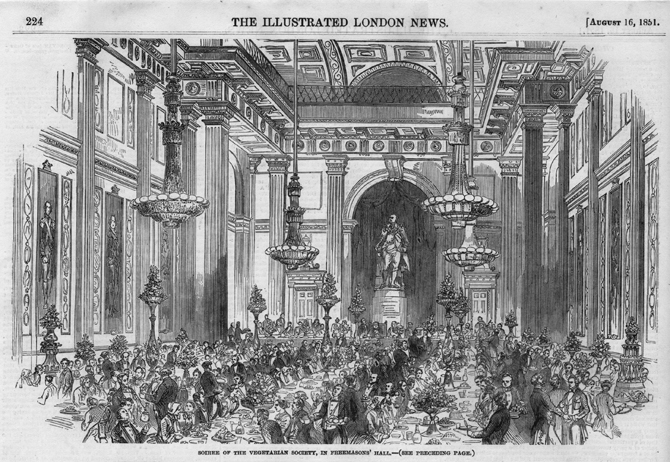

« Members of the Légumiste Society attend their yearly banquet in an increasingly satisfactory state of health. » (Le Charivari, 16th November 1853)

It is even more certain that vegetarians were extensively ridiculed at the time, and often the reluctant heroes of works on eccentrics. Their leader, sometimes referred to as the “chef des légumistes”, was partially responsible for this situation. Jean-Antoine Gleizes, who died in 1843, just after publishing his major work Thalysie ou la Nouvelle Existence (1840-42), tended to rewrite history in accordance with his personal views.  According to Edmond Texier, the writer Gérard de Nerval was also an eccentric and “a great supporter of légumisme [5], but in the manner of Pythagoras”. This did not stop Nerval from defending the Fatted Ox parade to which he was invited by a butcher in 1850 [6]. He not only attended the fair but made a speech on metempsychosis implying that animals had inner human souls (according to Texier, Nerval claimed to remember his own previous lives as a sheepdog and even a fatted ox). He ended his speech to the astonished butchers by asking them to replace the fatted ox with a fatted bean. The defenders of the ox inspired the cartoonist Cham to publish a sketch (in Charivari, 3rd February 1856) showing a man on all fours in the midst of a carnival procession with the caption: “A member of the Animal Protection Society who has obtained permission to replace the ox and spare him a tiring walk.” Cham had started to pick on légumisme in 1853 with talented cartoons of sad and scrawny vegetarians (see illustration). The real or imagined eccentricities of the légumistes delighted humorists and writers who tried their best to outdo each other.

According to Edmond Texier, the writer Gérard de Nerval was also an eccentric and “a great supporter of légumisme [5], but in the manner of Pythagoras”. This did not stop Nerval from defending the Fatted Ox parade to which he was invited by a butcher in 1850 [6]. He not only attended the fair but made a speech on metempsychosis implying that animals had inner human souls (according to Texier, Nerval claimed to remember his own previous lives as a sheepdog and even a fatted ox). He ended his speech to the astonished butchers by asking them to replace the fatted ox with a fatted bean. The defenders of the ox inspired the cartoonist Cham to publish a sketch (in Charivari, 3rd February 1856) showing a man on all fours in the midst of a carnival procession with the caption: “A member of the Animal Protection Society who has obtained permission to replace the ox and spare him a tiring walk.” Cham had started to pick on légumisme in 1853 with talented cartoons of sad and scrawny vegetarians (see illustration). The real or imagined eccentricities of the légumistes delighted humorists and writers who tried their best to outdo each other.

“A member of the Animal Protection Society who has obtained permission to replace the ox and spare him a tiring walk.” (Le Charivari, 3rd February 1856)

The fashion for table tapping spread through France in 1853, giving rise to surprising associations such as spiritualists and légumistes. A year later Edmond Texier related in the Revue de Paris that a vegetarian séance had instructed a member of the French Academy and his fellow spiritualists to abstain from eating any animal flesh and to eat only plants. In Mystic France, subtitled “Picture of religious eccentricities of our time”, Alexandre André Jacob (known as Erdan) deals with table tappers and légumistes alike. Gradually even doctors refer to the now fairly established relationship: “[…] exaggerated légumisme causes nervous system anaemia: as Gaëtan Delaunay notes, most exclusive vegetarians become spiritualists [7]” (Ernest Monin, L’Hygiène de l’estomac).

As early as 1854, regular French dictionaries endorse the new meaning of légumisme in a variety of contexts without referring to its familiar and pejorative connotation:

- La Châtre’s Dictionnaire universel is publically favourable to the légumistes. The original meaning (market gardening) is dealt with in one line while 25 more endorse the new sense. However, the definition is fairly restrictive as a “person who lives exclusively on vegetables”.

- Littré’s Dictionnaire de la langue française (1869) is not quite so enthusiastic: “Name of an English sect who eat only vegetables and abstain from any living thing [8].”

- The Grand Dictionnaire universel du xixe siècle (1873) bases its definition on Littré’s but replaces sect by association and vegetables by plants: “member of an association which imposes the obligation to live on a purely plant based diet: the Society of LÉGUMISTES.” The term légumiste was current at the time.

- Bilingual dictionaries and French for Foreigners guides [9] were also starting to use it. It is also used, for instance, by Adolphe Marsais [10] in the major Quebec daily the Canadien on 22nd December 1858:

“See the léguministe [11]

Who rejects meat and fish

And like the Indian Buddhist,

Makes water his only drink.

[…]

To each his own!”

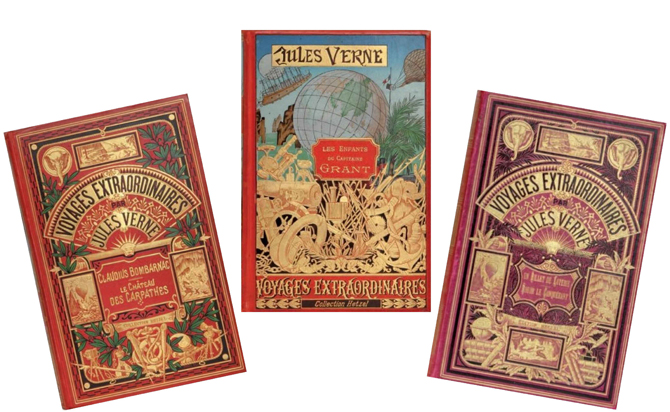

Major authors also adopted the word légumiste, led by Jules Verne first in Les enfants du capitaine Grant [12] (1868), then in Robur-le-Conquérant (1886):

“Jem Cip was a convinced vegetarian, one of those légumistes, those proscribers of all animal foods and fermented liquors, half Brahman, half Muslim, a rival of the Newmans, Pitmans, Wards and Davies who characterise this sect of those harmless loonies.”

And finally Claudius Bombarnac (1892):

“There burns the eternal fire, kept for hundreds of years by Parsee priests who came from India and never eat any animal food. In other countries, these vegetarians would simply be referred to as légumistes.”

These quotes demonstrate the pejorative connotation of the word légumiste, despite some genuine vegetarians such as Élisée Reclus using the term to describe themselves:

These quotes demonstrate the pejorative connotation of the word légumiste, despite some genuine vegetarians such as Élisée Reclus using the term to describe themselves:

“In my capacity as a légumiste, I pass as a magician at the Aruacos… [13]”

The word végétarien did not have that connotation, but would not be endorsed by dictionaries before 1876 (in the Larousse dictionary supplement) and 1877 (Littré). Its neutrality supplants its rival, for which substitutes are soon proposed: “[…] the Vegetarian Society, which one wag dubbed légumière or légumiste and which deserves to be called the Society of Herbivores [14]”. Towards the end of the 19th century the Nouveau Dictionnaire encyclopédique universel illustré still endorses légumiste, while advising: “better, végétarien”. The 20th century sounds the death knell of légumiste. From the very first edition (1906), the Petit Larousse indicates that the word is uncommon, though it only disappears from its pages altogether in 1948.

Finally, let us examine the exact meaning of the word légumiste and its link with veganism. The earliest occurrence and definition seems to be an article in the Journal des débats by John Lemoinne (1851):

“complete abstinence on principle from all animal foods.”

The author claims that légumistes “live entirely on vegetables [15]”. According to Oscar Comettant, the American légumiste club, which he dubbed “the starvation club”, has five principles, the two first being:

- « Do not kill animals.

- Do not eat meat or anything that comes from animals. However, the légumistes agree to permit milk for newborns. Some dissidents even allow it for themselves, arguing that milk has nothing to do with flesh.” (Oscar Comettant, L’Amérique telle qu’elle est.) »

The reason why an exception was made for infants is not clearly stated, but in the absence of B12 supplements it may have been a health measure [16]. In any case, these two examples only denote an Anglo-American origin of the concept of légumisme while the word itself is clearly French.

Jean-Antoine Gleizes was the main promulgator of the « herbal diet” in France (1842), though according to André Jacob it remained theoretical whilst it was actually put into practice in England. The diet promoted by Gleizes allowed some animal foods (milk and honey), unlike the above definition of légumisme. However, this requires some qualification as John Lemoinne describes a légumiste banquet where cheese pies and milk are served… This may also just be a conflict between two trends. The Methodist founders of the Vegetarian Society in England extended the concept to allow some animal by-products whereas the original creators and promoters of the word vegetarian excluded milk and honey [17].

The coexistence of two words, légumiste and végétarien, to describe someone who lives on a plant based diet might have led to the rapid disappearance of the first. On the contrary, however, as végétarien extends to allow some animal products such as milk, eggs and honey, légumiste is reinforced in its original meaning. In the lntermédiaire des chercheurs et curieux, Atomus therefore specifies (10th July 1883):

“Végétarisme and Légumisme (which is just one of its elements) are not to be confused. Végétarisme excludes only products from slaughtered animals. It accepts milk, eggs, cheese, honey, herbs, vegetables and fruits as foods.”

A few years later, Dr Bonnejoy (literally “good joy”) whilst being uncompromising with semi-vegetarianism, which he describes as semi-necrophagous none the less warns against “pure vegetarianism or sectarian légumisme”:

“In these circumstances, monobromisme végétalien or légumisme would be a mistake (many people confuse these with vegetarianism) and in effect and from a health point of view would apply only to poor communities who cannot afford vegetarian substances.” (Ernest Bonnejoy, Le Végétarisme et le regime végétarien rationnel.)

It is interesting to note that légumiste features next to végétalien. In the 1890s, the latter becomes widely used (as many dictionary entries show) and eventually supplants légumiste. Unlike veganism, none of the entries seems to focus on rejection of animal exploitation, but légumisme may sometimes go beyond dietary concerns when, for example, gutta-percha or rubber was discussed as a leather substitute [18].

The Légumiste of the Bastille (vegan vegetable retailer).

In memory of historic incivilities and to preserve cultural history, the president of the French Vegan Society has currently revived the word légumiste, but this remains a shining exception.

Tristan Grellet (Les Mots du végétarisme)

Translated by C. Imbs

—————————————————————-

NOTES

1. Contrary toLe Grand Larousse de la langue française and Le Grand Robert de la langue française,both repeat the Französisches Etymologisches Wörterbuch’s mistaken claims, légumiste does not feature in the Dictionnaire pour la théorie et la pratique du jardinage (Roger Schabol, 1767). Instead, we find the « légumier« , a gardener « whose sole concern is to grow vegetables ». Légumiste does occur in isolation in La physique des arbres (1758). In 1771, Le Dictionnaire de Trévoux states « why should we not say légumiste just as we say florist or tree grower? »

2. Except as an adjective in the expression « Pythagorean diet », popularised in 1750 by the translation of Antonio Cocchi’s Del vitto pitagorico (1743).

3. Respectively in the Jesuit review La Civiltà cattolica and in Schweizerisches Correspondenzblatt für Aerzte und Apotheker, a Swiss medical publication for military use.

4. In his Dictionnaire de la langue verte, the following definition is proposed: « Person who out of respect for the animals lives solely on vegetables like a virtuous Brahmins. There is a Légumiste Society. » Thirty years later, in his Dictionnaire argot-français et français-argot, George Delesalle considers the term to be popular.

5. His correspondence, however, reveals that he was still eating meat in 1843.

6. As a consequence of the February 1848 revolution, the fatted ox parade was banned for two years in Paris and took place on the outskirts. The probably quite ancient fatted ox carnaval involved parading a richly decorated bovine through the town before slaughtering it.

7. The absence of vitamin B12 supplements (isolated in 1948) makes the reference to anaemia quite relevant, but the evocation of spiritualism raised comments among readers even at that time: “With all due respect to the kind populariser, I must question that strange assertion. To enlighten myself on the subject, I should like to know in which work Gaëtan Delaunay’s develops the proposal and to see whether the author has not simply found an easy chance for ridicule.” (lntermédiaire des chercheurs et curieux du 10th November 1888)

8. In the 1877 supplement, the definition of végétarien is much more sober: « one who lives solely on vegetables. »

9. French for foreigners teaching method.

10. He may have imported the term since he was a French wine merchant from Charente who established himself in Canada in 1854.

11. Léguministe is a rare variation of légumiste. Léguminivore also exists but applies only to animals.

12. « For as long as the Maoris are not members of the Légumistes Society, they will eat meat and their meat will be human flesh. »

13. In a letter to his mother (14th October 1856), Reclus uses differently légumiste and végétarien indifferently.

14. François-Vincent Raspail, Natural History of health and illness.

15. John Lemoinne translates Vegetarian Society into Société des légumistes. As he seems to hesitate, the translation may be his: « This society calls itself the Vegetarian Society, or in other words Société des légumistes. » This proposition will become very popular for several years as the French translation of Vegetarian Society. Jules Verne will even use it in In Search of the Castaways (see note 12).

The use of the French word légume to translate the word English vegetable is not satisfying. As John Davis notes in « The vegetus myth », the meanings of these words have changed over time. The English vegetable had a broader sense than today and could be used to describe all kinds of plants while the French légume was more restrictive than it is today (« correctly used, it denotes certain seeds which come from pods, such as peas, broad beans, etc. » Dictionnaire de l’Académie française, 1835), though it is unlikely that the légumistes lived on peas and broad beans alone.

16. Vitamin B12 was not isolated until 1948.

17. John Davis, Extracts from some journals 1842-48 – the earliest known uses of the word ‘vegetarian’, from IVU website: http://www.ivu.org/history/vegetarian.html.

18. This point is raised in a speech by Vegetarian Society president James Simpson (see « Vegetarian banquet at Leeds » in « Chronique » in Le Mémorial français. Histoire de l’année. 1854).

BIBLIOGRAPHIE

- Académie française, Dictionnaire de l’Académie française, 2 vol., J. J. Smits, 1798, et Firmin Didot, 1835.

- Bonnejoy (Ernest), Le Végétarisme et le régime végétarien rationnel, Jean-Baptiste Baillière et fils, 1891.

- Cocchi (Antonio), Du régime de vivre pythagoricien, Frères Cramer, Claude Philibert, 1750.

- Comettant (Oscar), L’Amérique telle qu’elle est, Achille Faure, 1864.

- « Cronaca contemporanea », dans La Civiltà cattolica, Uffizio centrale della Civiltà cattolica, 1851 (vol. VII).

- Davis (John), « The vegetus myth », dans VegSource Interactive, VegSource.com [en ligne], mercredi 1er juin 2011.

- —, « Vegetarian equals vegan ! », dans VegSource Interactive, VegSource.com [en ligne], mercredi 7 juillet 2010.

- Delesalle (Georges), Dictionnaire argot-français et français-argot, Paul Ollendorff, 1896.

- Delvau (Alfred), Dictionnaire de la langue verte, 2e éd., Édouard Dentu, 1866.

- Dictionnaire universel françois et latin, 8 vol., Compagnie des libraires associés, 1771.

- Duclos (Henri Louis), « Archéologues de l’Ariège », dans Histoire des Ariégeois, s. n., 1886 ; t. II.

- Duhamel Du Monceau (Henri-Louis), La Physique des arbres, Hippolyte-Louis Guérin, Louis-François Delatour, 1758 ; vol. II.

- Esquiros (Alphonse), « Les excentriques de la littérature et de la science », dans Revue des Deux Mondes, Bureau de la Revue des Deux Mondes, 1846 (vol. XV).

- Gleizes (Jean-Antoine), Thalysie ou la Nouvelle Existence, 3 vol., Louis Desessart, 1840-1842.

- Gregory (James), Of victorians and vegetarians. The vegetarian movement in nineteenth-century Britain, Tauris Academic Studies, 2007.

- Grellet (Tristan), « Végétarien et végétalien », dans Les Mots du végétarisme [en ligne], mercredi 18 mai 2011.

- Intermédiaire des chercheurs et curieux (L’), L’Intermédiaire des chercheurs et curieux, 1883, 1888.

- Jacob (Alexandre André), La France mystique, Coulon-Pineau, [1855] ; vol. II.

- « Journalnotizen », dans Schweizerisches Correspondenzblatt für Aerzte und Apotheker, Haller, 1852 (vol. III).

- La Châtre (Maurice), Le Dictionnaire universel, 2 vol., Administration de la librairie, 1853-1854.

- Larousse (Pierre), Grand Dictionnaire universel du xixe siècle, 17 vol., Administration du Grand Dictionnaire universel, 1866-1877.

- Lemoinne (John), dans Journal des débats, vendredi 29 août 1851.

- Littré (Émile), Dictionnaire de la langue française, 4 vol., Louis Hachette, 1863-1869.

- —, Dictionnaire de la langue française. Supplément, Hachette et Cie, 1877.

- Marsais (Adolphe), « À chacun sa marotte », dans Le Canadien, mercredi 22 décembre 1858.

- Monin (Ernest), L’Hygiène de l’estomac, Octave Doin, s. d.

- Nerval (Gérard de), « Le bœuf gras », dans L’Artiste, L’Artiste, 1839 (vol. II).

- —, Œuvres complètes, Gallimard, 1989 ; vol. I.

- Nouveau Dictionnaire encyclopédique universel illustré, sous la dir. de Jules Trousset, 7 vol., Librairie illustrée, 1885-1891.

- Oxford English Dictionary [en ligne], Oxford University Press, 2011.

- Paillardet (Pascal), « C’est trop bio ! », dans La Vie, jeudi 9 juin 2011.

- Petit Larousse illustré, Larousse, 1906 (2004), 1941, 1948.

- Raspail, François-Vincent, Histoire naturelle de la santé et de la maladie, Librairie nouvelle, 1860 ; vol. III.

- Reclus (Élisée), Correspondance, 3 vol., Schleicher frères, Alfred Costes, 1911-1925.

- Richer (Jean), Nerval. Expérience et création, Hachette, 1963.

- Sandras-Fraysse (Agnès), « 1856 vu par Le Charivari : année bestiaire ou année zoo ? », dans Sociétés et représentations, Nouveau Monde, avril 2009.

- Schabol (Roger), Dictionnaire pour la théorie et la pratique du jardinage, Debure père, 1767.

- Texier (Edmond), « Chronique hebdomadaire », dans Le Siècle, dimanche 18 février 1855.

- —, « Revue du monde », dans Revue de Paris, Revue de Paris, 1854 (vol. XX).

- Vanderburch (Émile) et Brainne (Charles), « Un banquet de légumistes », dans « Chronique », dans Le Mémorial français. Histoire de l’année. 1854, Firmin Didot frères, 1855.

- « Vegetarian banquet at Leeds », dans The Times, mercredi 26 juillet 1854.

- Verne (Jules), Claudius Bombarnac, Jules Hetzel, [1892].

- —, Les Enfants du capitaine Grant, Jules Hetzel, [1868].

- —, Robur-le-Conquérant, Jules Hetzel et Cie, 1886.

- Viatte (Auguste), « Les origines françaises du spiritisme », dans Revue d’histoire de l’Église de France, 1935 (vol. XXI, no 90).

- Wartburg (Walther von), Französisches Etymologisches Wörterbuch, Zbinden Druck und Verlag AG, 1978 ; vol. IV.